To tree or not to tree: Comparing paper products to cotton

How much of what we consume began its life as a tree? A paper napkin or towel, a coffee filter, a notebook—were they once part of an oak, a maple, a pine or a fir?

Trees are, to an extent, a renewable resource. We can replant and regrow them. In some ways, using trees for paper products is also affordable. But the costs and sustainability depend a great deal on how much we use. If we consume paper products faster than trees can grow, then the process is not sustainable. And if we have to pay the costs over and over again because we cannot resume the products, then it ceases to be affordable, too.

Of course, there are alternatives—most notably cotton. And reusable cotton products are readily available. But are they better? More sustainable? More affordable?

This article explores the difference between using tree-based paper products and cotton-based alternatives for everyday products. Behind each purchase we find a complex web of costs: financial, environmental, and even social. Let’s take a look.

A tale of two fibers: How trees & cotton become products

From trees to tissue

Paper products start with wood pulp, usually from fast-growing trees like pine or spruce. The pulp is processed, bleached or unbleached, pressed, and dried into paper — a process that’s “cheap” compared to the returns on the investment. In other words, manufacturers can sell the paper products for more than the monetary costs of production. That’s why paper remains the dominant material for disposable goods.

But there’s a catch — even sustainable forestry requires land, energy, and water, and can disrupt ecosystems if not carefully managed. As this article will explore, the costs are far greater than simply the upfront money it costs to produce paper products or the money required to purchase a single paper product.

From cotton fields to cloth

Cotton, on the other hand, is a soft, cellulose-rich fiber grown mainly in warm climates like the southern United States, India, China, and parts of Africa. Cotton fibers require ginning, spinning, and weaving before becoming the familiar napkins or towels we use.

Unlike paper, cotton items are usually reusable. A cloth napkin or towel might last hundreds of washes, spreading its environmental and financial costs over years instead of minutes. Yet cotton farming can be resource-intensive, in conventional, non-organic agriculture, demanding significant water and pesticides.

Organic cotton farming changes that equation. By avoiding synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, organic growers protect soil health and preserve surrounding ecosystems. They also often rely on less water intensive growing methods, including rainwater harvesting and maintaining the soil health, which preserves its ability to hold water. Of course, these measures have higher upfront costs than non-organic cotton farming.

Comparing the costs: Paper versus cotton

Let’s set aside for a moment the fact that most cotton products are reusable and simply ask how much an individual product costs to make. And when discussing “costs” we’ll limit ourselves to money for now (don’t worry - you know we’ll get to the environmental costs in this article, too).

What the manufacturer pays

According to Natural Resources Canada, bleached hardwood kraft pulp typically ranges from $1,400 to $1,800 per metric ton, while cotton linters pulp is often $1,700 to $2,200 per ton, making cotton pulp roughly 15–25 percent more expensive on average.

What the consumer pays

At the checkout counter, the price difference is just as clear:

Paper napkin: roughly $0.03 each in the U.S.

Cotton napkin: about $1.10–$1.20 each, or ~$14 for a 12-pack.

Paper coffee filter: around $0.02–$0.05 each.

Cotton coffee filter: roughly $10, reusable hundreds of times.

That might make cotton sound more expensive — but when we zoom out over time, the math changes dramatically.

Cost per use: The long view

It’s tricky to know exactly how much a product costs over the long term—but it’s easy to understand that some products are meant to be thrown away after a single use and others can be used over and over again. So, let’s imagine a typical four-person household in the U.S. and estimate the use of each type of product.

Napkins

If each person uses two paper napkins per meal, that’s roughly 2,920 napkins per year. At $0.03 each, that’s $87.60 per year.

Switching to reusable cotton napkins costs maybe $30 up front for two dozen. If they last five years, that’s $6 per year, plus a few dollars in extra laundry costs. Even adding $10 a year for washing, cotton still totals about $15–20 annually — far less than the recurring paper expense.

Towels

The same principle applies to towels. Paper towels might cost a few dollars per roll, but over a year of regular use, a household can easily spend $100–$150 replacing them. A good set of cotton dish towels costs $20–$30 and can last for years.

Coffee Filters

When it comes to coffee filters, the difference is even starker. We’ve done plenty of research suggesting that cotton filters—even the higher-priced organic cotton—is still less expensive than paper over time, not to mention much less waste.

In the calculations below, we’re using the average price of paper filters alongside the price of our own CoffeeSock product, $14 for two filters ($7 each).

In the case of coffee, a reusable filter pays for itself after just a few weeks of daily brewing. And it keeps thousands of paper filters out of landfills over its lifetime.

The hidden costs: Energy, water, and waste

Trees and the paper trail

Producing paper products requires harvesting, pulping, bleaching, and drying — all energy- and water-intensive processes. Globally, the pulp and paper industry consumes about 4 percent of all industrial energy use and contributes significantly to wastewater and chemical pollution.

Even sustainably managed forests carry environmental trade-offs. Monoculture tree plantations, while efficient, can reduce biodiversity and alter soil health. Each ton of virgin paper emits roughly 1.5 tons of CO₂ during production and distribution.

Cotton’s thirst and footprint

Non-organic cotton has a different problem: water. According to the World Wildlife Fund, it takes an estimated 2,700 gallons of water to grow enough cotton for a single T-shirt. Conventional cotton farming also accounts for 16 percent of global insecticide use and 7 percent of pesticide use.

Organic cotton offers a meaningful improvement. By avoiding synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, organic systems protect soil health, biodiversity and water use. However, yields are typically lower, meaning it takes farmers using more land or more time, sometimes both, to produce the same amount of fiber. And while organic cotton can reduce water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions by up to 40–50 percent compared to conventional cotton, the overall water and energy use can still vary widely depending on specific regional practices and processing methods.

When comparing cotton and paper, it’s helpful to look at how long the product lasts, in addition to its costs.

Water and emmissions over a product’s life

Napkins: A case study

While cotton—both conventional and organic—requires significant water to grow, we use the end product hundreds of times, spreading that water cost out over years. Paper products, by contrast, are typically single-use, so even though the water required to produce one paper napkin is much lower than a cloth napkin, we then throw it away and grab another.

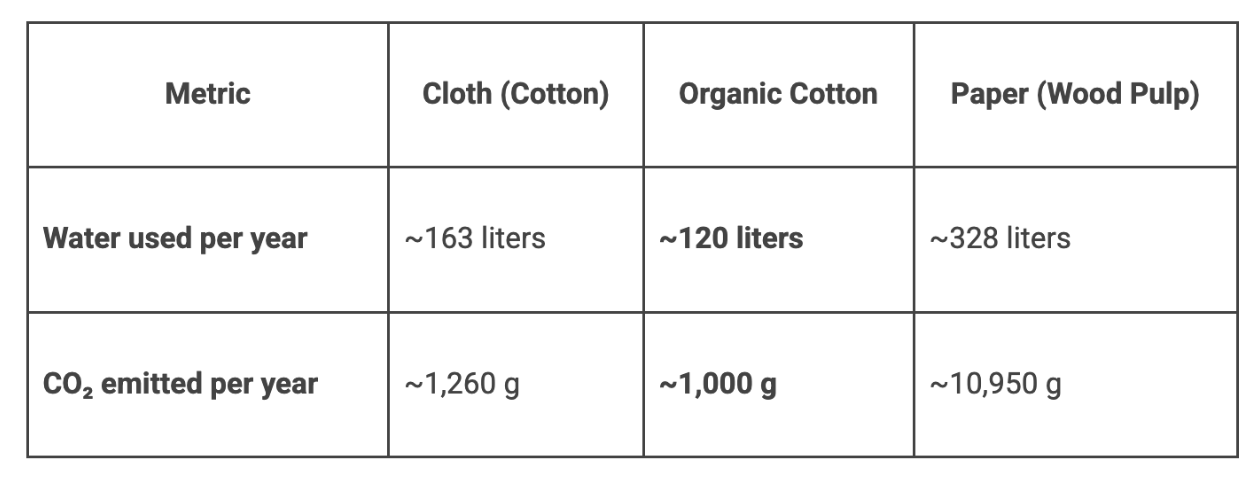

One environmental comparison by Ichcha, a sustainable textile company, estimated the total yearly footprint of napkin use, including the water required to produce and wash.

In other words, even accounting for laundering, a household that reuses cotton napkins emits about one-tenth the carbon and uses roughly half the water compared to using paper napkins daily.

Coffee filters: A case study

The environmental footprint of a paper coffee filter is relatively small in a single brew — but multiplied by billions of cups brewed each year, it adds up. A typical paper filter’s lifecycle includes tree harvesting, pulping, bleaching, and disposal. Even when composted, paper filters represent a steady stream of one-use materials.

By contrast, reusable cloth filters like CoffeeSocks have a higher manufacturing footprint upfront but nearly zero ongoing material waste. If used for 1,000 cups, the per-use carbon and water costs drop to a fraction of a disposable filter’s footprint.

What about water and washing?

One common criticism of reusable cotton items is the water and energy used in laundering. But in most households, napkins or towels simply go in with regular laundry, meaning little to no additional cost or footprint.

Let’s put some numbers on it:

Washing one load of laundry in a modern, efficient washer uses 15–30 gallons of water.

Adding a dozen napkins increases total use by perhaps 1–2 gallons per week — a negligible fraction.

Even if we add the cost of detergent and energy, it’s small compared to the ongoing production, packaging, and transport of paper products.

Choosing wisely: A quick, practical guide

You might choose tree-based paper when:

Convenience and hygiene matter, such as in a medical setting.

The product is unbleached, made from recycled paper, and compostable.

You have access to composting.

Use cotton, especially organic when possible, when:

You can reuse the item many times, such as napkins, towels, and coffee filters.

You can wash or launder effectively. .

You value durability, texture, and reducing long-term waste.

The bottom line

Here’s a handy recap chart.

If you’re only looking at the cost you pay at the checkout counter, paper looks cheaper. But once you factor in repeat purchases and waste, cotton often wins over time. Environmentally, cotton, especially organic cotton, is the clear winner.

Conclusion: Spend less. Waste less.

The choice between paper and cotton isn’t just about cost — it’s about what kind of consumption you want to support. Paper is about convenience and disposability; cotton is about sustainability.

In the end, that’s the real value. Not just in dollars saved, but in a lasting shift toward a life that wastes less and feels better.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “State of the World’s Forests 2020: Forests, Biodiversity and People,” 2020.

International Energy Agency, “Tracking Industry 2022: Pulp and Paper,” 2022.

Natural Resources Canada, “Pulp prices (weekly, nominal, USD/tonne),” 2024

Pesticide Action Network, “Cotton and Pesticides: A Global Perspective,” 2017.

Soil Association, “Organic Cotton: Reducing the Footprint of Fashion,” 2022.

Textile Exchange, “Organic Cotton Market Report,” 2023.

Water Footprint Network, “The Water Footprint of Cotton Consumption,” 2022.

World Wildlife Fund, “The Impact of a Cotton T-Shirt,” 2013.